Visit deflock.me to see an open source map of FLOCK cameras in your area, to submit a camera, or to get involved.

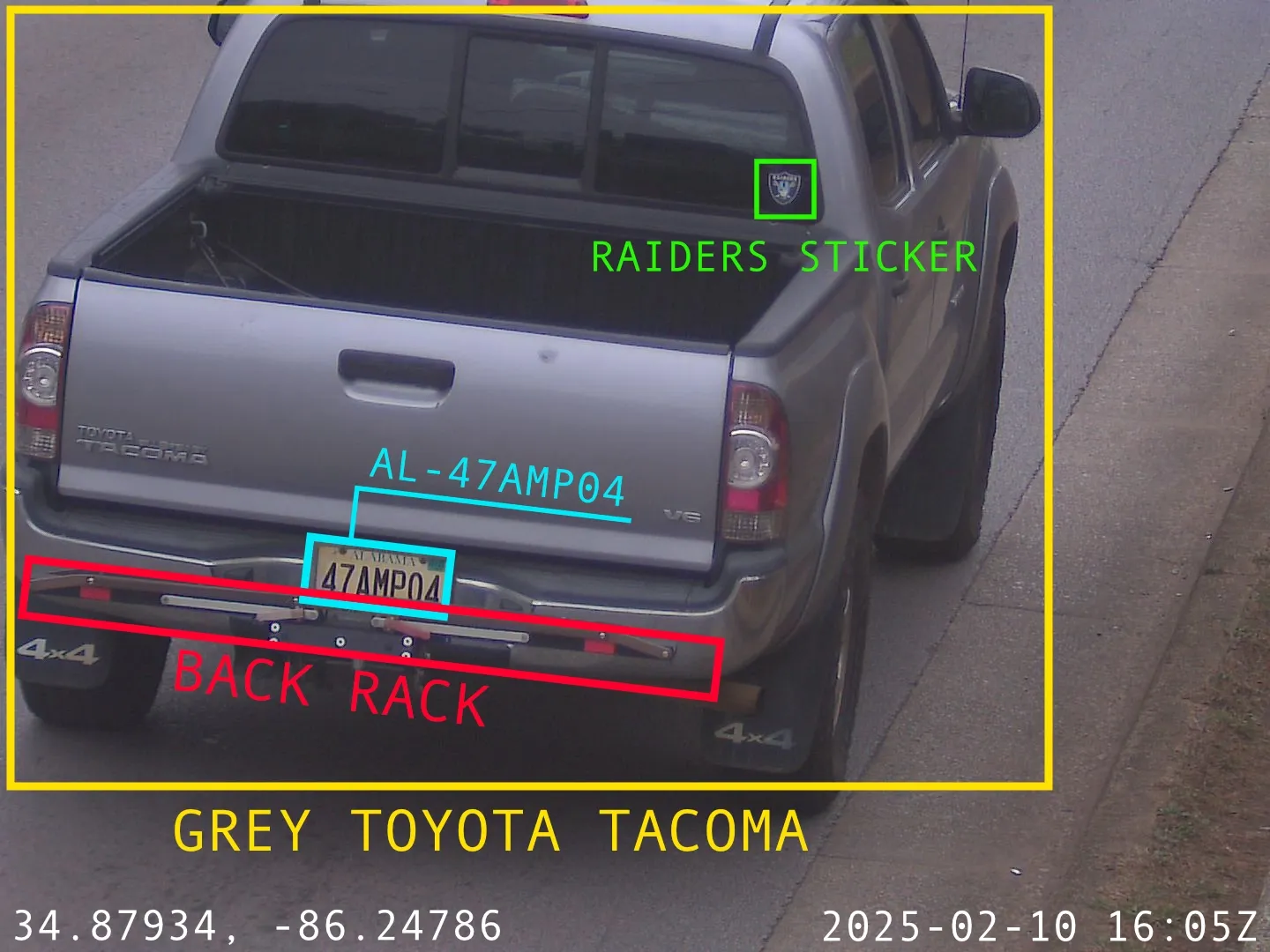

Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs or LPRs) are AI-powered cameras that capture and analyze images of all passing vehicles, storing details like your car's location, date, and time. They also capture your car's make, model, color, and identifying features such as dents, roof racks, and bumper stickers, often turning these into searchable data points.

These cameras collect data on millions of vehicles regardless of whether the driver is suspected of a crime. These systems are marketed as indispensable tools to fight crime, but they ignore the powerful tools police already have to track criminals, such as cell phone location data, creating a loophole that doesn't require a warrant.

Flock (sometimes styled as “FLOCK”) is a small‑to‑mid‑scale aerospace company that designs and sells these cameras, in addition to drones equipped with high‑definition camera systems.

Criticisms and Legal Concerns

The deployment of Flock cameras—and the broader trend of commercial drones for law‑enforcement purposes—has sparked a flurry of criticism on several fronts:

- Privacy and Fourth‑Amendment Rights

Critics argue that any ALPR or UAV capable of recording video at 4K resolution or above can easily capture private property and individuals in a way that violates the reasonable‑expectation‑of‑privacy standard. A number of U.S. states have enacted or are debating legislation that requires prior judicial authorization (or at least a “probable‑cause” notice) before a police agency may deploy a drone for surveillance. The use of Flock drones in the 2022–2024 protests in cities such as Minneapolis and Portland drew media scrutiny, with protesters accusing law‑enforcement of “sweeping up footage of demonstrators without consent.” - Data Retention and Security

Flock’s cloud‑based data portal allows users to store and annotate footage in the cloud, raising concerns about who can access that data and for how long. In a 2023 audit of a state police department that had recently adopted Flock drones, the department’s data retention policy did not specify a clear deletion timeline, leading civil‑rights watchdogs to call for tighter controls. Additionally, a 2024 report on the security posture of consumer‑grade drones identified vulnerabilities in the firmware update process, suggesting that Flock cameras might be susceptible to remote hijacking if the vendor’s security patch cycle is lax. - Lack of Oversight and Transparency

While the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) sets air‑space rules for all drones, many local agencies use Flock cameras without a robust public accountability framework. Critics point out that unlike traditional ground‑based surveillance, aerial footage can cover larger geographic swaths and is often captured with little real‑time notice to residents. This has prompted calls for publicly accessible logs of drone flights, flight‑path maps, and data‑sharing agreements with third‑party vendors. - Use in Targeted Law‑Enforcement Operations

A handful of cases have emerged where Flock drones were used in “targeted” operations, such as following a suspect during a burglary or monitoring a specific individual at a protest. While the company maintains that its systems are “intended for general reconnaissance,” these incidents fuel a broader debate about “surveillance capitalism” and the potential for drones to become tools of predictive policing. Critics argue that the low cost and relative ease of deployment mean that a large number of agencies could, intentionally or not, conduct covert surveillance that crosses constitutional lines.

Easily Exploitable

In December 2025, YouTuber Benn Jordan exposed severe security vulnerabilities in Flock Safety’s automated license plate reader (ALPR) cameras, demonstrating how they could be compromised with minimal technical skill. Jordan’s research revealed that Flock cameras could be accessed by pressing a button on the device to create a Wi-Fi hotspot, enabling unauthorized access to the camera’s data and allowing remote control. This vulnerability, combined with the exposure of livestreams and administrative panels for at least 60 AI-powered Condor cameras across the U.S., raised significant privacy and security concerns.

- Flock Safety’s ALPR cameras were found to be vulnerable to physical access exploits, where pressing a specific button sequence on the device creates a Wi-Fi access point that allows attackers to enable ADB (Android Debug Bridge) and gain full control over the device.

- Jordan demonstrated that these vulnerabilities could be exploited to install malicious software, exfiltrate data, or use the cameras as honeypots to steal login credentials.

- In addition to physical access exploits, at least 60 of Flock’s Condor PTZ cameras were left exposed to the open internet without any password or login, allowing anyone to view real-time footage, access 30 days of archived video, and modify camera settings.

- Jordan also discovered that Flock cameras could be tricked into not recording license plates by applying small visual noise patterns to the plate, a technique that prevents AI recognition while remaining readable to humans.

- Flock Safety’s CEO, Garrett Langley, responded by claiming the company had never been hacked and accused critics of spreading misinformation, while also sending cease-and-desist letters to websites mapping Flock camera locations.

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and other privacy advocates have criticized Flock’s practices, highlighting the risks of mass surveillance without adequate security or public consent.

What about the constitution?

In most jurisdictions, laws explicitly prohibit actions that disrupt or interfere with Automatic License Plate Recognition (ALPR) cameras, often with broad language that could encompass even passive or defensive measures. These laws are designed to prevent any form of interference with the operation of surveillance systems used by law enforcement. For example, attempting to block or obscure a license plate in a way that prevents accurate reading by ALPR systems may be considered illegal, even if the intent is privacy protection. Some jurisdictions have specific regulations requiring that license plates remain unobstructed and free from dirt or foreign material so they can be accurately photographed by traffic enforcement devices. While there is no universal federal law governing ALPR use, individual states have implemented varying levels of regulation, with some enacting strict penalties for unauthorized access or misuse of ALPR data. However, legal challenges continue to emerge, with courts in states like Washington affirming public access to ALPR data collected by third-party vendors such as Flock Safety, highlighting ongoing tensions between surveillance practices and transparency.